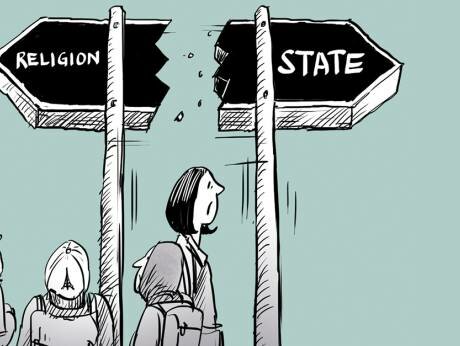

Like many countries all over the world, Egypt is committed to the principles of Islam. Article 2 of the 2014 Constitution provides that “the principles of the Shari’a are the main source of legislation”. Its preamble provides, however, that the reference of its interpretation is found in the corpus of the jurisprudence of the Constitutional High Court.

Egypt’s modern legal system was initially developed in the 19th century and was modelled after the French Napoleonic Code. However, various modifications and adaptations were introduced to yield the current Egyptian version of the French system. Egyptian law combines religious and civil laws. In practice, judges are invited to fill the gaps therein by following the principles of Islamic law. Egypt’s Civil Code governs the areas of personal rights, contracts, obligations, and torts.

In the Egyptian system, free access to the courts and legal aid is a constitutional provision and equal access to justice is often cited as a fundamental right. However, this access is out of the reach of many disadvantaged persons and communities, including minority groups, due to a lack of affordable legal representation. The Egyptian legal system recognizes the necessity of granting access to the courts and the provision of legal aid for those who lack the necessary means. These principles have been affirmed and guaranteed by a wide array of legislative instruments, including the Egyptian Constitution, which provides that “litigation is a right that is safeguarded and an inalienable right for all. The State shall guarantee the accessibility of judicature for litigants and rapid adjudication on cases.”

However, the minority concept is not recognized before the law in the Egyptian case as the State claims prima facie that it is in contradiction with the principles of equality. Nevertheless, for some minorities with numerical significance such as Copts some special arrangements have been made including specific laws (that yet fail to include the entire range of rights granted to the minority). Other minorities have still not been granted such arrangements or guarantees.

The new Egyptian Constitution, adopted by referendum in January 2014, was presented by the Egyptian government as a revolutionary Constitution, a model for the protection of human rights and a significant step towards a democratic transition. It came at the close of a particularly chaotic constitutional transition that began with the fall of President Hosni Mubarak on February 11, 2011.

Despite the fact that opposition groups complained about intimidation and lack of impartiality in media coverage, for the country’s most vulnerable communities, however, the drafting process provided at least an opportunity to promote a more inclusive environment for Egypt’s diverse religious and ethnic population. During the months preceding the referendum, representatives of long-marginalized minorities such as Amazigh and Nubians were able to meet with members of the drafting committee to advocate for various amendments to the text.

Members of minorities (Copts, Nubians, Amazighs…) actively participated in the drafting of Egypt’s new constitution, which led to the recognition of the cultural diversity in the country under article 50 that recognizes diversity and that states:

“Egypt’s civilization and cultural heritage, whether physical or moral, including all diversities and principal milestones—namely Ancient Egyptian, Coptic, and Islamic—is a national and human wealth. The State shall preserve and maintain this heritage as well as the contemporary cultural wealth, whether architectural, literary or artistic, with all diversities. Aggression against any of the foregoing is a crime punished by Law. The State shall pay special attention to protecting components of cultural pluralism in Egypt”

The 1971 Constitution had already adopted affirmative actions, but the 2014 Constitution extended the list of guaranteed rights even further. It more effectively protects women’s rights and sets up mechanisms for positive discrimination against minorities. In addition, it has introduced anti-discriminatory protections that prohibits discrimination based on religious beliefs, sexual orientation, origin, race, ethnicity, language, disability, social class, political or geographic affiliation or any other reason.

Additionally, the Egyptian State is committed to develop a plan for the economic and urban development of border regions and disadvantaged areas within ten years, including Upper Egypt, Sinai, Matrouh and Nubia, taking into account the cultural and environmental patterns of local communities (section 236).

However, effective protection of human rights requires the establishment of concrete implementation and oversight mechanisms by the Constitution, and the 2014 text does not provide sufficient guarantees in this area. Therefore, there is continued scepticism around the government’s willingness and ability to tackle the broader context of discrimination towards minorities throughout the country.

Moreover, due to the lack of clear and effective mechanisms to guarantee the exercise of citizenship rights by minorities, the situation of minorities in Egypt changes with the change in political leaders and their condition varies according to the trends of the ruling power.

Barriers to Justice

The barriers faced by members of minority groups can be divided into two main points: legal hindrances, and State practices.

1. Legal hindrances

a. The Constitution:

The 2014 Constitution was presented as an important step towards larger protection of human rights and the establishment of a civil state respectful of minorities. It was generally regarded as a break with the past and an adjustment of that of 2012, passed under former President Mohamed Morsi, presented as the Constitution of a theocratic state, and coming under criticism from human rights activists for not protecting minority groups. The analysis of its content, and in particular the provisions relating to human rights and those dealing with the identity of the State, shows, however, that it is more a continuity than a break with the Egyptian constitutional order. While it shows progress in terms of proclaimed rights, there remains a lack of mechanisms needed to be implemented to ensure compliance with these provisions.

Although the country is home to many ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities, the word “minority” itself never appears in the Egyptian Constitution.

While articles 47 and 48 provide that: “The State shall maintain the Egyptian cultural identity with its diversified branches of civilization” and that “Culture is a right to every citizen. The State shall secure and support this right and make available all types of cultural materials to all strata of the people, without any discrimination based on financial capability, geographic location or others. The State shall give special attention to remote areas and the neediest groups.”, article 2 of the Constitution provides that: “Islam is the religion of the State and Arabic is its official language.”

b. Compliance with international law

The relationship with international treaty bodies, the process for signing, ratifying and incorporating international instruments into national legislation as well as their status in the legal hierarchy of the State is part and parcel of a modern constitution. Traditionally, national legal systems follow two different procedures for incorporating international law into the national legislation: monism and dualism. Countries with a civil law system are more likely to have adopted monism. The Constitution of Egypt has also adopted monism and international conventions are assumed to be part of national law. Consequently, the national judge can immediately apply the provisions of the convention. Article 93 of the 2014 Constitution provides that: “The State shall be bound by the international human rights agreements, covenants and conventions ratified by Egypt, and which shall have the force of law after publication in accordance with the prescribed conditions.”

However, through its reservations Egypt frequently adopts international human rights conventions while “taking into consideration the provisions of the Islamic Sharia and the fact that they do not conflict with the text annexed to the instrument …” Such reservations have often been criticized for their lack of clarity.

2. The practices of the State and its organs

At best, the Egyptian judicial system has dealt with its minorities in a fragmented manner, if at all. This has produced a system in which minority issues are not all developed as justiciable issues. Even when the rights that are explicitly codified and court decisions are issued, the application on the ground by the concerned services and the follow-up of cases is not effective as the minority communities are not sufficiently represented at the level of the police services and administration at large.

Other rights that have been codified with reference to equality of all Egyptian citizens before the law in accordance to international treaties may have not been granted equal implementation for minorities due to the lack of recognition of minority groups.

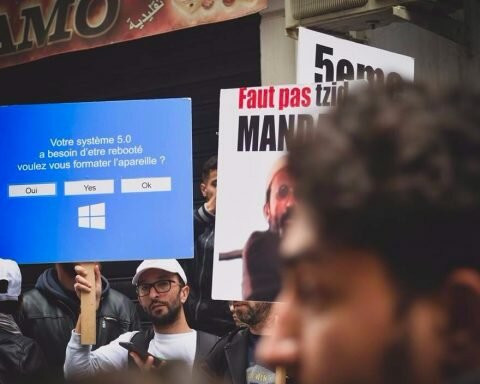

In recent years, hundreds of civil society groups have been dissolved while others have had their assets frozen and travel bans imposed on their members. This has been enabled by measures such as the 2013 anti-protest law, 2015 anti-terrorism law and 2016 NGO law. The latter is particularly worrying as many Egyptian NGOs that work with international partners provide essential services, including education and health care, in the country. Funding from foreign sources is subject to close monitoring and requires official approval. NGOs will need government permission before working with foreign organisations and will have to notify the authorities before receiving any foreign funds.

In a press release of June 1st 2017, this new NGO law was deemed “Repressive” and “deeply damaging for human rights in Egypt” by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein. He further said that “the issuance of a repressive new law further restricting space for human rights monitoring, advocacy and reporting by non-governmental organisations would be deeply damaging for the enjoyment of human rights and leave rights defenders even more vulnerable to sanctions and reprisals than they already are.”

Minority Rights violations since 2014

Despite the high hopes raised by the 2014 constitution, the situation of minorities in Egypt remains unenviable. Christians still struggle for permission to build churches, and are the target of sectarian violence and attacks by Muslim extremists. Systematically, they face unfair informal dispute resolution mechanisms that often result in the displacement of community members from their homes to only appease the minds of extremists.

In addition, many Nubian activists have been imprisoned following demonstrations against the government’s decision to sell part of what remains of their ancestral lands to investors for an agricultural megaproject. They still continue their long wait to return to those lands as indigenous people in Egypt.

Bedouin communities in North Sinai are caught between the extremists of ISIS and the ferocious repression of the Egyptian armed forces. They face a growing humanitarian crisis caused by mass displacement and widespread violence.

Meanwhile, religious minorities such as Bahá’i, Shi’a, Ahmadis and Quranists still struggle for recognition, making it difficult for them to practice their religion freely.